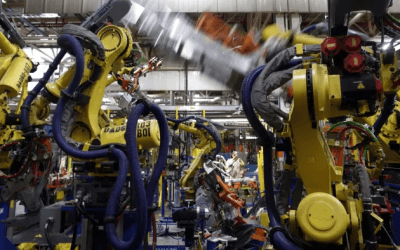

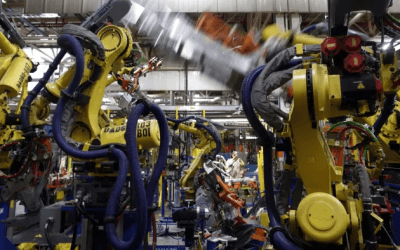

Pace of automation depends on how easily workers are displaced

Variables that will affect the rate of adoption of robots and smart machines are huge

Barack Obama had a parting shot for his successor this week. A day before Donald Trump predicted he would be “the greatest jobs producer that God ever created”, the outgoing US president appeared like the ghost at the feast, warning of “the relentless pace of automation that will make many jobs obsolete”.

It is at least possible that both will be proved right. Automation has been a constant for decades, and the latest advances in robotics and artificial intelligence all but guarantee that the pace will accelerate. But timing is all. For companies and their investors — no less than for politicians — the key question is not “whether”, but “when”.

For society at large, the pace of automation will determine how easily the displacement of workers can be handled — and whether the political backlash grows worse. The pace is equally important for the companies trying to push the latest robots and smart machines into the real world, and their investors. Few are in the position of Google parent Alphabet, which has taken the long view on bets such as driverless cars — and even Alphabet these days has a new sense of impatience about when it will see returns from “moonshots” like this.

The variables that will affect the rate of adoption are huge. In a new report on automation this week, McKinsey estimates that half of all the tasks people perform at work could be automated using technologies that have already been proven. But this estimate gives no clue about how long it will take.

Given the uncertainties about everything from regulation to the ability of companies to change their processes, the consultants estimate it could take anything from 20 to 60 years. Try building an investment model with that level of variability.

Take the case for autonomous cars and trucks. Much of the technology has already been demonstrated, and the potential markets — for both vehicle makers and tech suppliers — are vast. But will it take five, 10 or 30 years for this to become a significant market?

Car companies are spending hundreds of millions of dollars on building driverless car platforms. At this month’s Consumer Electronics Show and Detroit Auto Show, it was clear that driverless technology has graduated from the experimental: carmakers are now racing to bring this technology to the roads. The biggest companies are able to amortise this cost over a large vehicle fleet, but the increasing level of technology in vehicles will challenge many of the industry’s smaller players.

Companies like Audi talk of autonomy as a progression. It says some 60 per cent of new car buyers already opt to pay $3,000-$6,000 for features such as automated acceleration and braking. Those customers might reasonably be expected to keep paying up for additional levels of safety and convenience. The shift from cars that stay in their lanes automatically to hands-off-the-wheel driving might turn out to be a smooth — and profitable — evolution.

But the strongest business case for driverless cars comes from the more radical, all-or-nothing step of eradicating the need for human drivers. In a report on automation’s impact on the economy late last month, the White House said that most of today’s 1.7m drivers of heavy trucks in the US are likely to be replaced — though it added that “it may take years or decades” for this to happen.

There are some very practical considerations. As Michael Chui, a partner at McKinsey, points out, it is vastly expensive to replace the estimated 2m heavy trucks on US roads, with an average lifespan of 20 years. Even without new driverless technology, McKinsey estimates it would cost $320bn.

But there are likely to be specific investment cases for speedier adoption. Long-haul routes are the low-hanging fruit of trucking. Platooning, in which trucks form a convoy behind a lead truck driven by a human, could bring a form of supervised automation. Although the long-tail of automation may take decades, the market for early adopters could still be vast.

Rather than wiping out jobs immediately, progressive automation might make the lives of today’s truckers more comfortable and then make up for an expected driver shortage in the mid term, before eliminating jobs eventually. This prospect represents the rosy scenario for the companies leading the AI and robotics charge. But as today’s turbulent political climate shows, they would be foolish to count on such a smooth transition.